Fluency. When we think of stuttering, we might first think of speech therapy, of pauses and repetitions, and of the courage it takes to speak when words get stuck. But what if we could step back and see its genetic architecture laid out across the globe? A recent study looked at the genetics of stuttering at an unprecedented scale: over 1.1 million individuals, including almost 100,000 people who self-reported a history of stuttering. Stuttering shows a significant overlap with other neurodevelopmental disorders and enrichment of genes expressed in the brain. Here is a brief summary of one of the most important studies in stuttering research in the last few decades.

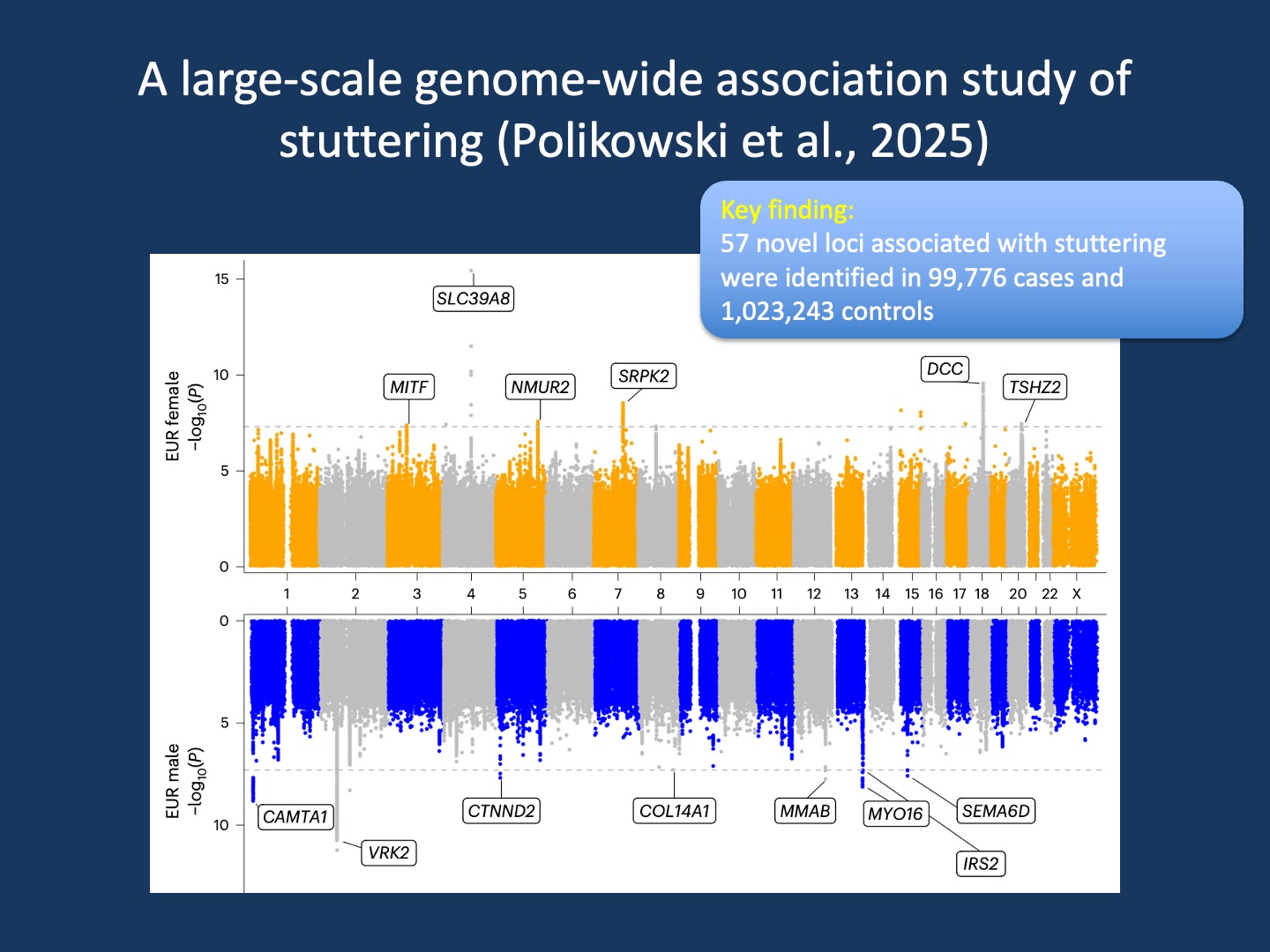

Figure 1. Miami plot of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for stuttering in females (top) and males (bottom) of European ancestry. The female GWAS analyzed 570,071 individuals (40,137 cases), identifying nine genome-wide significant loci. The male GWAS included 374,279 individuals (38,257 cases), identifying ten such loci. The x-axis shows genomic coordinates (hg19), the y-axis the −log10(P) values from logistic regression. Dashed lines mark the significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). Genes shown are predicted functional candidates for each locus from the Open Targets Genetics V2G pipeline. This side-by-side view highlights both shared and sex-specific genetic architecture in stuttering (modified from Polikowsky et al, 2025 under a modified from Polikowsky et al., 2025 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Stuttering. Before I introduce stuttering and the challenges in conceptualizing this condition, I wanted to briefly highlight one key aspect of human speech that we typically take for granted – the fact that it works smoothly most of the time and we do not realize it. We typically think about words and then they simply come out of our mouth, almost in the same way that the words that I am thinking about appear on the screen before me when I type them. Therefore, fluency disorders where typical speech is interrupted by blocks, pauses, or interruptions feel unusual – and I am saying this as a person who stutters. It turns out there is much more complexity to it.

Transparency. Speech production is part of the bodily self-model: your brain predicts and monitors the movement of your tongue, lips, larynx, and breathing, while also integrating auditory feedback. This speech self-model is normally transparent – you do not consciously track every tongue placement or breath timing; instead, you just “speak” and experience the intended words flowing out. Because it is transparent, attention can focus on what you say, not how you say it. But there is an enormous machinery at work. And when you try to disentangle stuttering, you have to look under the hood.

Demosthenes. In 2013 I started blogging about the genetics of stuttering referring to Demosthenes, the ancient Greek orator. Demosthenes was said to have treated his speech impediment by talking with pebbles in his mouth and shouting above the roar of the ocean waves. Stuttering, or stammering in British English, is a fluency disorder in which speech is disrupted by repetitions, prolongations, or abnormal pauses. Frequent dysfluencies can severely impair communication. Many people develop secondary symptoms such as eye-blinking or tic-like movements, and the struggle to “get something out” is often stressful and socially disruptive. Stuttering can lead to fear of public speaking, low self-esteem, social phobia, and depression.

Take a breath. Despite well-meant advice to “just take a breath,” it is a disability accompanied by stigma, often reinforced by mocking portrayals in films like Life of Brian, A Fish Called Wanda, or, for German-speaking readers, Helge Schneider’s Texas. Stuttering is more common in men. Transient childhood dysfluencies are distinguished from Persistent Developmental Stuttering (PDS), which persists into adulthood. While stuttering usually cannot be cured, it can be managed. I have had the honor of giving an overview of the biology of stuttering to the participants of the Woody Starkweather Intensive Stuttering Program over the last few years and I have come to realize that providing some clarity of what stuttering is can be extremely helpful. There are few medical conditions that are associated with so much misunderstanding, stigma, and shame.

The genetics of stuttering. There is a strong genetic component to stuttering, which is known from twin studies and family studies. However, in contrast to many other neurodevelopmental conditions, the genetics of stuttering is poorly understood. We and many others have realized that the recruitment of people who stutter for genetic studies is challenging. Therefore, the recent publication by Polikowsky and collaborators in Nature Genetics is unique. The authors took advantage of the now-defunct 23andMe dataset and included a total of 99,776 cases and 1,023,243 controls for a genome-wide association study. The vast majority of individuals with stuttering were self-reported, which is important to keep in mind when understanding the results of the study. However, prior studies in other neurological disorders such as in migraine have shown that the sheer size of the study compensates for some inaccuracy. Here are three main findings of the study by Polikowsky and collaborators.

1 – No Demosthenes gene. What studies of that size can reliably estimate is the effect size associated with common genetic variants. We know from numerous studies that there are no common monogenic causes of stuttering and that many of the proposed genetic causes are not reliably validated. However, could there be strong common variants that increase the risk substantially, as in autoimmune disorders or conditions such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD)? The answer is no. Even though Polikowsky and collaborators find 57 distinct genetic loci associated with stuttering that are all novel to the field, none of the loci increase the risk by more than 1.05-fold. No smaller study would be able to capture this amount of risk. While the sum of all associations is strong enough to explain roughly 10% of its heritability, stuttering is highly genetically heterogeneous, and there is no single Demosthenes gene.

2 – Overlap with autism. Given that thousands of GWAS have been performed, it is relatively straightforward to compare the overlap of genetic risk factors. One of the most striking findings from the study by Polikowsky and colleagues is how interconnected the genetics of stuttering is with other traits, including many outside the realm of speech and language. Using genetic correlation analyses, the team identified significant overlaps with autism, ADHD, depression, and hearing loss, pointing to shared neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric pathways. But the list does not stop there. Stuttering genetics also intersected with body mass index, asthma, daytime sleepiness, and alcohol consumption frequency, which are traits that may harbor broader systemic or behavioral links. Perhaps most intriguingly, the study confirmed a strong connection with beat synchronization, the ability to align movements to an external rhythm, and walking pace, both of which tie into the motor timing systems that have long been suspected to play a role in stuttering. Together, these findings reinforce that stuttering is not an isolated condition in the genome. It shares a web of genetic influences with traits across the neurological, psychiatric, metabolic, and motor domains. This hints at the fact that the story of stuttering is also the story of brain and body timing, coordination, and development.

3 – What the genes point to. The study by Polikowsky and colleagues found both shared and distinct genetic signals between males and females, echoing the known sex differences in stuttering prevalence and recovery. Certain genes stood out, including VRK2, CAMTA1, SLC39A8, DCC, and SRPK2 in addition to functional enrichments pointing to neuronal pathways. VRK2 and SRPK2 are brain-enriched kinases linked to psychiatric risk and tau biology. In addition, VRK2 emerged early from the first epilepsy GWAS. CAMTA1 is a calcium-responsive transcription factor implicated in monogenic non-progressive congenital ataxia. Biallelic variants in SLC39A8, a manganese transporter, are the cause for a congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG) with developmental delay, hypotonia, dystonia, and epilepsy. Finally, and most interestingly, DCC, the netrin-1 receptor, guides axons across the midline. Rare variants can cause mirror movements and corpus callosum agenesis. This suggests that the genetic risk for stuttering includes some genes where rare variants with strong effect size have been observed to cause monogenic neurological disorders. Also, I must admit that I have thought about writing a blog post about DCC and congenital mirror movements for almost a decade – I would have never thought that stuttering would give me the opportunity to accomplish this!

What you need to know. Polikowsky and colleagues performed a “millennium experiment”, exploring the genetics of stuttering through a well-powered genome-wide association study of almost 100,000 people who stutter and one million controls. The authors identified 57 novel loci that point towards neurodevelopmental processes and found an interesting overlap with other traits, most notably autism and impaired beat synchronization. This one-of-a kind study highlights that stuttering is not the product of a single faulty gene or pathway. Stuttering is a complex, polygenic trait with an underlying biology that overlaps with neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and even motor rhythm traits. Polikowsky and colleagues should be congratulated for shifting the focus of stuttering genetics from anecdotal reports and small family-based studies into the territory of large-scale, replicable science.