ANE. A rare complication with hidden genetic clues. Imagine a healthy child who goes to bed with a fever and wakes up unable to recognize their parents, slipping rapidly into coma. This is the terrifying course of acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), one of the most severe neurological complications of influenza. In a recent study, children with influenza who developed ANE showed an unexpected pattern: nearly half of those tested carried genetic variants that might predispose them to this devastating complication.

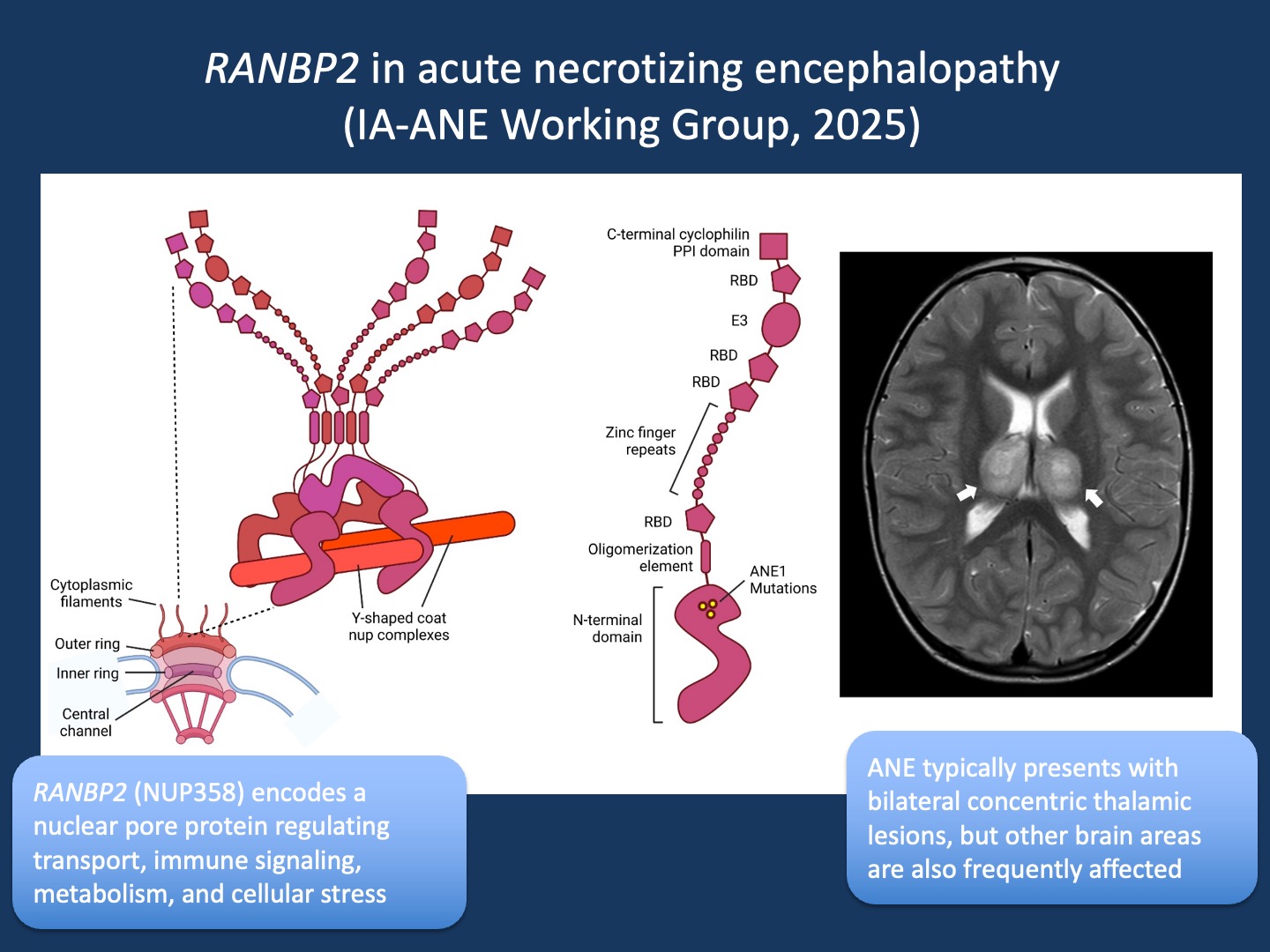

Figure 1. Function of RANBP2 and neuroimaging in ANE. Figure. Structural model of RanBP2/Nup358 and neuroimaging in acute necrotizing encephalopathy. RanBP2/Nup358 is a major component of the cytoplasmic filaments of the nuclear pore complex, which has an eightfold symmetry with each symmetrical unit referred to as a ‘spoke’. Five copies of RanBP2/Nup358 are found at each spoke, for a total of 40 copies per pore. The N-terminal domain attaches to the pore and is the spot where ANE1 mutations cluster. On the right, magnetic resonance imaging from a 3-year-old child presenting with a viral prodrome and rapid neurological decline. T2-weighted axial images demonstrate the characteristic bilateral thalamic lesions typical of acute necrotizing encephalopathy (figure adapted from Palazzo et al., 2022 under CC BY 4.0, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Influenza. A recent publication in JAMA by the Influenza-Associated Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy (IA-ANE) Working Group presents the largest US case series to date, capturing 41 children across 23 hospitals during the 2023–2025 flu seasons. Patients were mostly young (median age 5 years) and previously healthy (76%). The illness progressed at alarming speed: from fever to encephalopathy in just two days. Neuroimaging showed the classic bilateral thalamic lesions, often extending into the brainstem, and nearly all patients required intensive care. The outcomes were sobering: 27% of all ANE patients died, typically within three days of admission and often from cerebral herniation due to brain swelling. Among survivors, two-thirds were left with moderate to severe disabilities at 90 days, including spasticity, dystonia, epilepsy, and in some cases dependence on tracheostomy or feeding tubes. Only a minority (16%) had received influenza vaccination. Almost all were treated with multimodal immunotherapy and antivirals, reflecting the lack of standardized management guidelines. While the clinical findings, treatment approaches, and public health implications of the study are critical, I want to focus here on the genetics, which was only one part of the study but a striking and thought-provoking dimension.

RANBP2 and beyond. Among the entire cohort of 41 children, 11 (27%) were found to carry RANBP2 variants, either pathogenic or of uncertain significance. This number is remarkable given the severity of the phenotype and underscores why RANBP2 has become synonymous with ANE. Pathogenic variants in RANBP2 predispose to recurrent or familial episodes of encephalopathy triggered by viral infections, and this study reaffirmed its central role in that process.

Nucleoporin. RANBP2 (also known as Nup358) encodes Ran-binding protein 2, a large component of the nuclear pore complex that regulates the transport of proteins and RNA between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Disease-causing variants in RANBP2 are a recognized cause of ANE, but the mechanistic links remain only partly understood. Structurally, there is strong evidence that ANE-associated mutations destabilize a key domain of RanBP2 at the nuclear pore. RanBP2 also acts as an enzyme that attaches SUMO proteins to other proteins, switching their activity on or off. This tagging process helps keep inflammation under control: RanBP2-mediated modification of Argonaute proteins silences inflammatory messenger RNAs such as IL-6 and TNFα, while SUMOylation of STAT1 dampens type I interferon responses. When RanBP2 is mutated, these immune “brakes” may fail, leading to excessive cytokine release—the “cytokine storm” seen in ANE.

Mitochondria and beyond. Beyond immune regulation, RanBP2 also connects to mitochondria, influencing energy metabolism, stress responses, and autophagy, the recycling of damaged cellular components. Disruption of these pathways may make neurons especially vulnerable during viral infection. Adding another layer of complexity, viruses such as influenza often exploit nuclear pore proteins for replication. Mutations in RanBP2 may therefore tilt the balance toward uncontrolled immune activation in the face of infection. In summary, the best-supported mechanisms involve structural instability and loss of immune system brakes, while roles in mitochondrial dysfunction and virus–host interactions remain plausible but less certain.

Immune and metabolic connections. RANBP2 was not the whole story. Other single-gene findings broadened the discussion of how susceptibility to infection-triggered encephalopathy might arise. The other genetic findings were only found in individual patients but highlight possible mechanistic diversity. A single individual with biallelic variants in PRF1 stood out, as this gene is known to cause familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL2), an immune dysregulation syndrome in which CNS inflammation is often dominant. This provides a potential model of how impaired immune surveillance might lead to catastrophic encephalopathy. Single patients with SUOX, TBK1, and RNU4ATAC variants were also identified. In contrast to PRF1, SUOX variants cause sulfite oxidase deficiency, a metabolic encephalopathy not mediated by immunity but by toxic metabolite accumulation. TBK1, a kinase central to interferon signaling linked to a condition referred to as autoinflammation with arthritis and vasculitis (AIARV), raised questions about effects on innate immunity. Finally, RNU4ATAC, usually associated with syndromic genetic disorders, has recently been implicated in dysregulated interferon signaling, providing another plausible pathway connecting rare genetic syndromes with virus-triggered encephalopathy.

Neurodevelopmental genes. Other reported variants included SETD1A, THOC2, NEXMIF, SPTAN1, and FOXP1. These are well-established genes for neurodevelopmental disorders, linked to intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, or epilepsy. There is currently no evidence linking these genes to immune dysfunction or encephalitis. Their presence in the cohort is more likely coincidental than causal but requires further scrutiny in the future.

What you need to know. In a recent publication in JAMA, the clinical message was clear: ANE is a devastating complication of influenza with high mortality (27%) and major disability among survivors. Only a small fraction had received vaccination, underscoring a key prevention gap. Genetics was only one aspect of the study, but it was striking—nearly half the children tested carried variants of possible relevance, and 27% of the entire cohort harbored RANBP2 variants. While RANBP2 remains the primary gene associated with ANE, other findings in PRF1, SUOX, TBK1, and RNU4ATAC suggest that both immune dysregulation and metabolic vulnerability can converge on this phenotype. Variants identified in neurodevelopmental disorder genes are likely incidental but deserve further scrutiny. For me, the genetic angle stands out, as it highlights the intersection of host susceptibility and viral triggers: a theme that resonates with our thinking about rare diseases more broadly.