Evidence. I was a contributor to a recent commentary questioning whether the USP25 gene should currently be considered a validated gene for genetic generalized epilepsy. The motivation behind this commentary was not to challenge the initial data, but to ask what happens when a claim for gene validity encounters the full weight of accumulating evidence. Does USP25 remain robust as our expectations for validation rise? Or has it reached the point where additional evidence no longer supports the initial discovery?

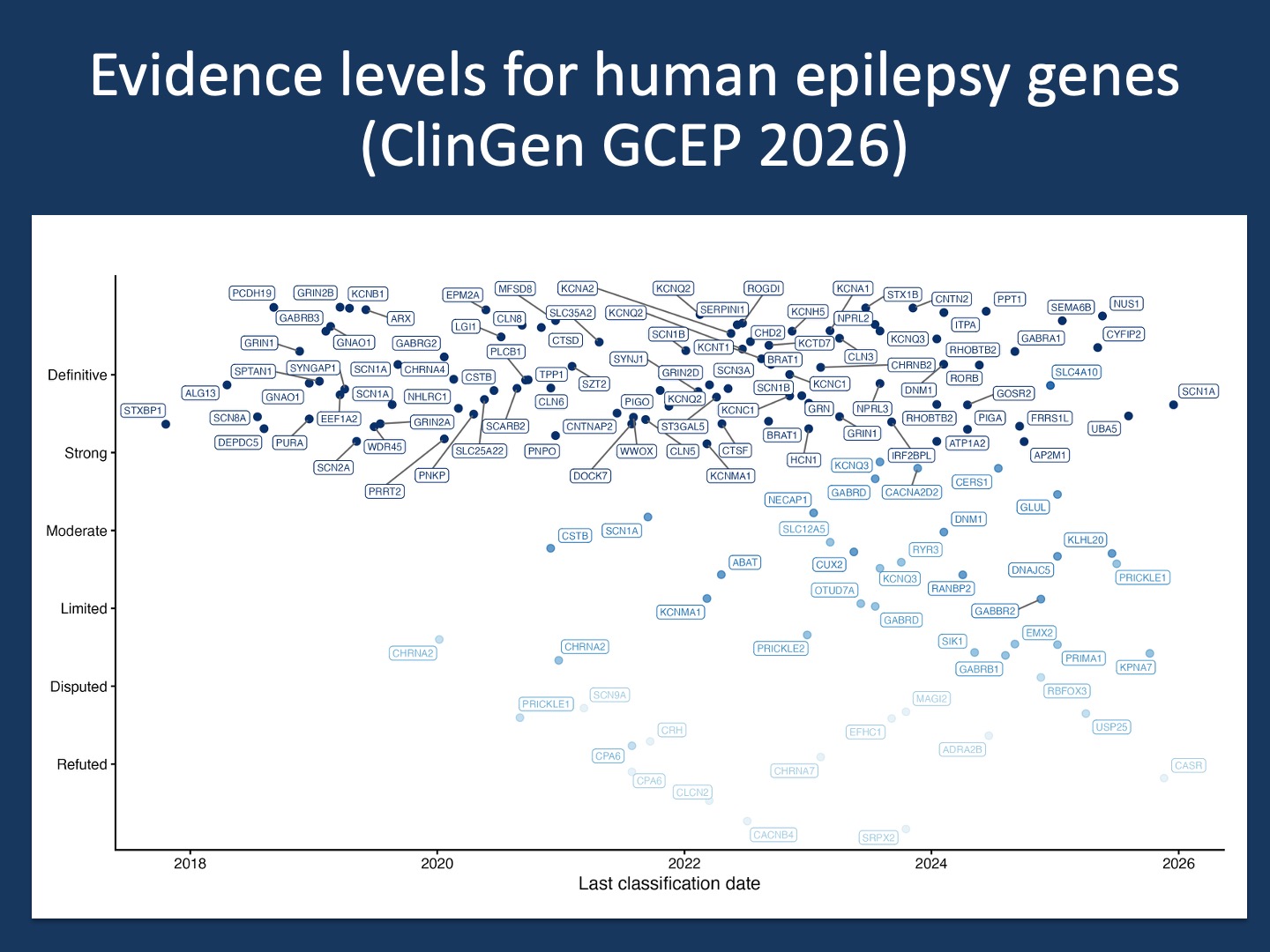

Figure 1. Each point represents a gene–disease assertion curated by the ClinGen Epilepsy Gene Curation Expert Panel, positioned by the date of its most recent evaluation and arranged vertically by strength of evidence. Darker blues indicate stronger support, with Definitive gene–disease relationships at the top and Refuted relationships at the bottom. The vertical spread reflects jitter added for visibility, emphasizing that evidence strength behaves more like a gradient than a set of rigid tiers. Gene labels are shown to highlight how individual genes move within this landscape of confidence. This is the broader context for USP25. Strength of gene-disease associations is not an isolated debate for any particular gene, but part of the ongoing process by which gene–disease claims are tested against accumulating data that either support or question validity. All gene–disease validity classifications shown here are publicly available through the ClinGen gene validity curation interface.

A gene under scrutiny. In an initial publication in Brain in 2024, Fan and collaborators suggested that variants in USP25 contribute to the risk for genetic generalized epilepsy (GGE). In our subsequent commentary by Omidvar and collaborators in collaboration with the Epi25 Consortium, we followed up on this initial investigation by examining population frequency data, rare variant association design, and the interpretation of functional experiments. We concluded that the available data do not justify categorizing USP25 as an established epilepsy gene or risk factor. This is not an argument against studying this gene further. It is an argument for precision in how we label genes once they begin to transition into the clinical field.

Gene discovery is provisional. In rare disease genetics, we often behave as if gene discovery were irreversible. A gene is published, added to panels, and quietly becomes part of the canon. But in reality, gene-disease assertions are hypotheses that evolve over time. Early on, when cohorts are small and background variation is poorly understood, claims can appear stronger than they ultimately prove to be. As datasets grow and expectations sharpen, some signals strengthen, while others become weaker. As with many aspects of science, some discoveries are validated over time, while others are contradicted by ongoing research. In a way, it would be strange if all initial gene discoveries held up over time. In one of our earlier blog posts, we suggested that genes should be allowed to respectfully “retire.”

The ClinGen framework. The tension between discovery and validation is exactly why the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) developed a formal gene-disease validity framework. In my role as Co-Chair of the Epilepsy Gene Curation Expert Panel (GCEP), we have worked on applying this framework across many epilepsy-associated genes, including revisiting claims that were once widely cited but insufficiently supported by replicated human genetics. ClinGen does not ask whether a gene is biologically plausible. We ask whether the totality of genetic and experimental evidence supports a causal relationship with disease.

Disputed and refuted are expected outcomes. Within the ClinGen framework, a gene-disease relationship can be classified as Disputed when newer evidence conflicts with earlier claims, or Refuted when the balance of evidence no longer supports causality. This has already happened in epilepsy genetics. Genes such as EFHC1, SRPX2 or CACNA1H were initially proposed based on limited cohorts or family studies and later failed to withstand larger-scale analyses. In other cases, genes were shown to cause different neurodevelopmental phenotypes than originally claimed, requiring the epilepsy association itself to be disputed or removed. These outcomes are not exceptional. They are part of how the field corrects itself.

Why this makes people uncomfortable. Gene names carry a certain momentum. A gene can become part of a diagnostic identity, influencing reporting and counseling. Therefore, when a gene-disease relationship is questioned, it can feel as though certainty is being withdrawn. But avoiding re-evaluation does not preserve clarity. It only delays the moment when uncertainty becomes explicit.

USP25 as an example, not a verdict. The discussion around USP25 should be understood as an illustration of this process rather than a final judgment. A candidate gene was proposed. A critique examined whether the evidence was sufficient to support it. A response defended the interpretation. This is what it looks like when a gene enters the phase where claims are tested against broader data rather than novelty. In our commentary, we expressed our concern that USP25 does not have sufficient evidence to be classified as a causative gene or risk factor for GGE, disagreeing with some of the initial assertions made by the authors. The ClinGen GCEP concluded that the evidence supporting the relationship between USP25 and autosomal dominant epilepsy has been disputed, and no valid evidence remains to support the claim.

Burden of proof. Epilepsy genetics has matured to a point where discovery alone is no longer enough. We now generate candidate genes faster than we can validate them. The credibility of the field depends on our willingness to revisit claims, revise gene lists, and accept that some early assertions will not endure. We have written before on Beyond the Ion Channel that precision medicine depends not only on finding genes, but on knowing which findings hold up when examined over time. Therefore, it is important to emphasize where the burden of proof lies. Given the increasing amount of genetic variation identified in the human genome, validation of gene-disease association is an uphill battle for each candidate gene. It is not on the field to disprove a gene-disease assertion. The burden of proof is on the research community to provide ongoing validation for a gene-disease claim.

What you need to know. Gene-disease associations are hypotheses that evolve as evidence accumulates. ClinGen provides a framework to determine when a claim is supported, when it becomes uncertain, and when it no longer holds. Some epilepsy genes have strengthened through this process. Others have been disputed or refuted. This is not a flaw in rare disease genomics. It is how the field maintains credibility while moving forward, which will be critical for targeted therapies in genetic epilepsies.