Decade. Over the past week, winter storm Fern has blanketed large parts of the United States with several feet of snow, leading to a virtual standstill in many regions. When I looked back, I realized that the last major snowstorm that paralyzed public life was a decade ago, a storm called Jonas. Snowed in exactly ten years ago, I reflected on the state of epilepsy genetics. Let’s see what has changed in the field since Jonas in 2016.

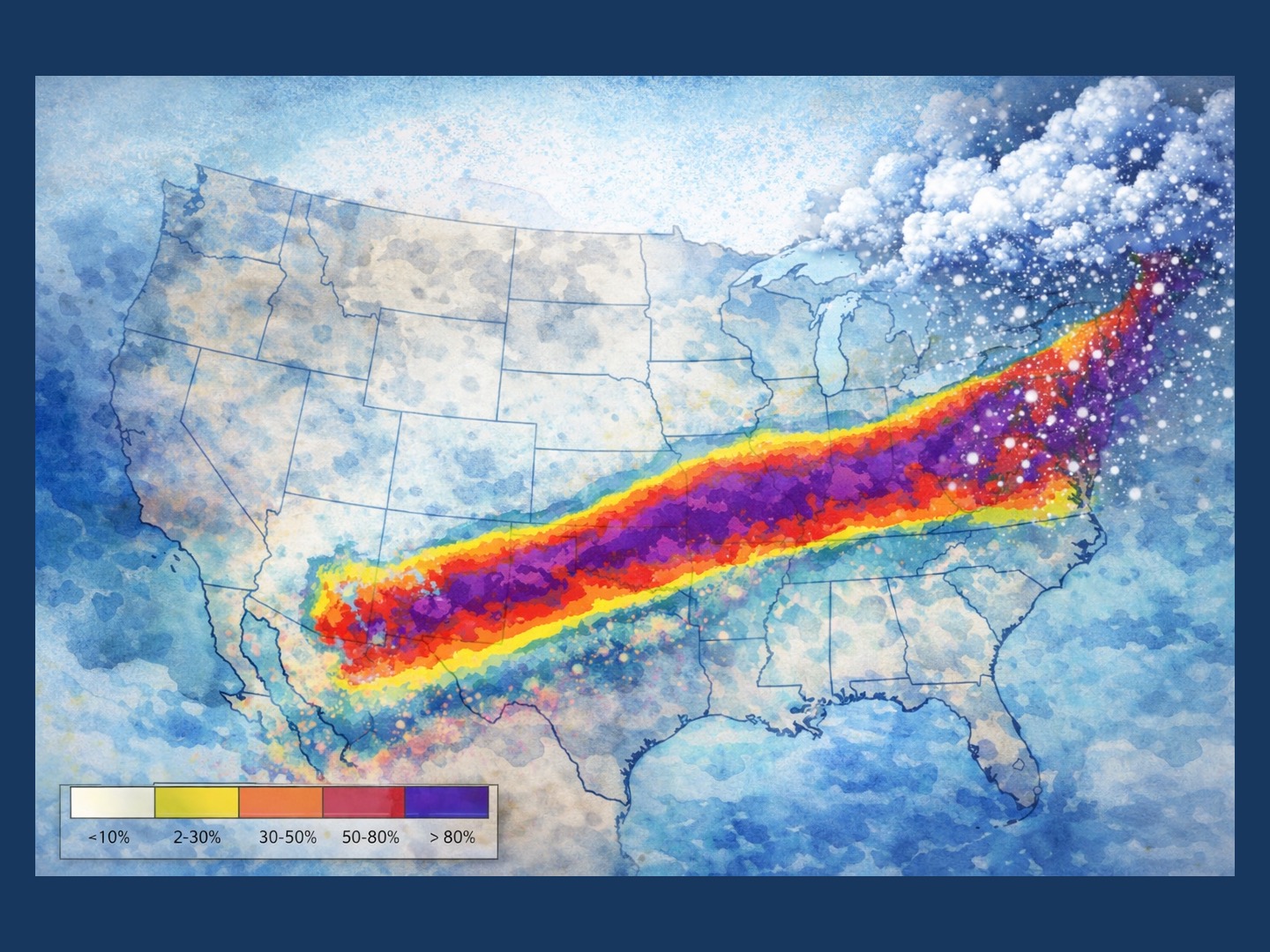

Figure 1. Artistic adaptation of a forecast map originally produced by the U.S. National Weather Service (NOAA). Colors indicate the maximum probability of exceeding warning criteria, meaning the likelihood that a given location will experience winter weather severe enough to trigger official warnings (such as heavy snowfall, ice accumulation, or dangerous travel conditions) at some point during the event. Warmer colors reflect a higher probability that warning thresholds will be met or exceeded. The map illustrates the expected large-scale impact pattern of Winter Storm Fern across the United States in January 2026, re-rendered here for conceptual and narrative purposes rather than operational forecasting.

Fern. I learned today that naming for snowstorms is not mandatory. In contrast to hurricanes, names for blizzards emerge somewhat organically. However, their effects on daily life are fairly predictable. For example, my apartment has a singular Achilles heel that anticipated Fern’s arrival: the water line in my kitchen froze, rendering my kitchen sink and dishwasher useless. Later that day, the shelves at our local supermarket were picked over. I grabbed one of the last gallon water bottles with It’s the End of the World as We Know It by R.E.M. and Hazy Shade of Winter by the Bangles playing overhead, which made me smile. Let me look back at five blog posts that we published around the time of Jonas’ arrival in 2016 and what has changed since.

Gene discovery. Back in 2016, I mused about the “novel gene dilemma.” This blog post was about the pace of gene discovery and how long it would take to move from individual discoveries to validation of disease entities. At the time, genes such as SON and PURA were still largely uncharacterized. Ten years later, both genes are long-established disease genes, moving toward precision medicine approaches with strong advocacy organizations. However, not every gene that we considered back then became an established disease gene. De novo variants in SV2A, for example, have rarely been detected since our 2016 blog post, even though the biology of this presynaptic vesicle protein has always been very interesting: it is the molecular target that levetiracetam acts on. In addition, ten years later, gene discovery is no longer limited by gene identification. With large-scale studies published over the last decade, there are hundreds of genetic epilepsies and neurodevelopmental disorders that remain uncharacterized. Gene discovery has become less an issue of capability and more an issue of focus.

PRRT2. It was PRRT2’s turn to be featured in the “This Is What You Need to Know” section of our blog, a series that we eventually abandoned given the rapid pace of the field. And even though it is one of the most common epilepsy genes, alongside SCN1A, we have written very little about PRRT2 over the last decade. It is a gene for a self-limiting infantile epilepsy that is relatively well understood. It is also not a candidate for major natural history study efforts or precision medicine treatments, given that the condition is typically self-limited and mild. However, there has been some interesting progress regarding PRRT2. While I had initially thought of it as a presynaptic modulator with a mildly inhibitory effect on SNARE complex zippering, more recent evidence suggests that PRRT2 negatively regulates sodium channels, in particular SCN2A and SCN8A. This function may explain the effect of sodium channel blockers in PRRT2-related epilepsy, turning PRRT2-related disorders from presynaptic disorders into an “indirect sodium channelopathy.”

Methusalem proteins. In my 2016 post, I made a reference to so-called Methusalem proteins. These are proteins in the human body that turn over very slowly over a lifetime. And it turns out that for some proteins, this turnover may effectively never occur. For example, most nucleoporins in the neurons of my brain are the same proteins as they were when I was born. Nucleoporins have clear disease associations in neurological disorders. For example, RANBP2, the causative gene for acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), is a nucleoporin and a Methusalem protein. Given that I recently wrote about RANBP2 and ANE, it is interesting to see how a previously abstract concept about protein turnover has clear disease relevance in 2026.

Areas of uncertainty. Another blog post that we published at the time of the Jonas blizzard in 2016 dealt with areas of uncertainty in epilepsy precision medicine. In contrast to the other posts listed above, this piece feels somewhat dated in 2026. We wrote about early insights into precision medicine, such as quinidine in KCNT1, a narrative that is rarely mentioned today. My reference to data-driven methods for understanding how individuals with milder SCN1A-related disorders respond to lamotrigine also sounds somewhat clumsy a decade later. Today, we would refer to either real-world data or real-world evidence. There are many areas of uncertainty in epilepsy genetics in 2026, but looking back at what I wrote back then, I can clearly see how both our language and our understanding have evolved.

Research parasites. Finally, it was interesting to reread my 2016 blog post on data sharing and “research parasites.” To clarify, this language was not my own; I was referring to an ongoing controversy at the time. In 2016, The New England Journal of Medicine warned of an emerging class of researchers labeled as research parasites—individuals who were not involved in the original study but reanalyzed data without connection to the initial study design. The editorial called for collaborative research conducted on a coordinated basis rather than independent analyses detached from the original investigators. Even at the time, the editorial was widely perceived as tone-deaf. Particularly in genetics, access to publicly funded datasets is often essential, and data siloing has long been a problem. Where are we ten years later? Large-scale genome sequencing studies are now readily available, and resources such as the UK Biobank and the U.S.-based All of Us program provide access to datasets that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. In contrast, linking existing datasets—such as genomic data—with deep clinical phenotyping has become the new frontier, along with the necessary discussions about balancing research value with privacy concerns.