Fusion. If you have ever tried to merge soap bubbles, you know the paradox. Soap bubbles look soft and fragile, but the moment you bring them close, they push each other away. Membranes behave similarly. A synaptic vesicle and the presynaptic membrane do not naturally want to merge. They repel each other. Therefore, synaptic vesicle release requires a mechanism that overcomes this resistance, holds two membranes in close contact, and then triggers fusion on demand within milliseconds. In a recent paper, that mechanism is brought into focus through UNC13A, a gene encoding one of the central priming factors that makes synaptic fusion possible. Here is what the study shows.

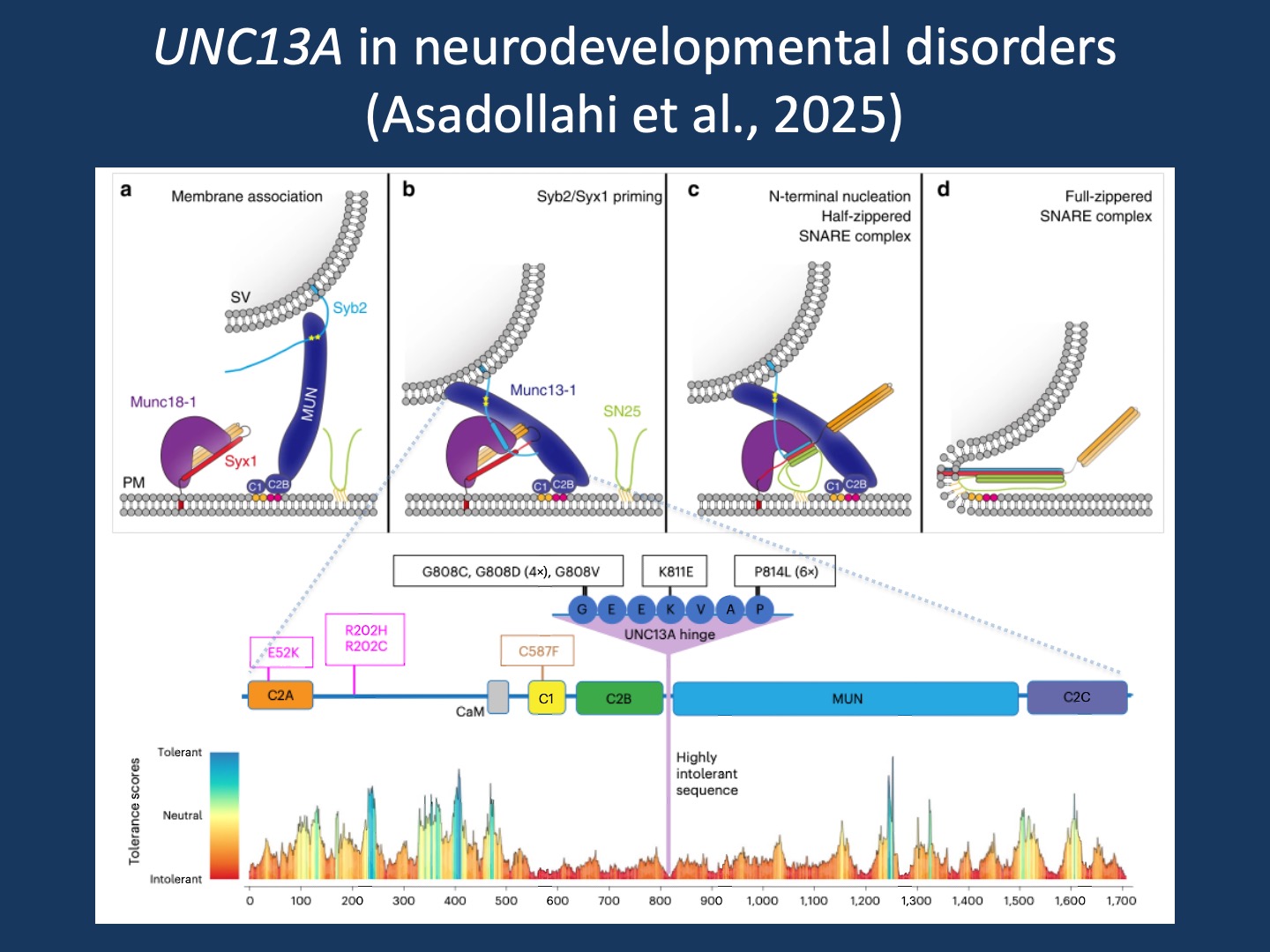

Figure 1. UNC13A (MUNC13-1) as a synaptic priming factor and the landscape of UNC13A missense variation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Top panels (a–d): Working model of the Munc18–Munc13 route to SNARE complex assembly during synaptic vesicle priming and fusion. (a) Membrane association and pre-alignment: interactions between synaptic vesicle synaptobrevin/VAMP2 (Syb2) and the MUN domain, together with C1–C2B binding to DAG/PIP2, position vesicles near the plasma membrane and facilitate engagement of the Munc18-1/Syntaxin-1 (Syx1) complex. (b) Priming: coordinated Munc18-1/Syx1/Munc13 interactions promote Syb2 binding and stabilize a primed intermediate. (c) Proofreading and nucleation: entry of SNAP-25 (SN25) supports N-terminal SNARE nucleation and formation of a half-zippered SNARE complex, releasing Syntaxin-1 from Munc18-1 clamping. (d) Completion: full SNARE zippering drives membrane merger and vesicle fusion. Adapted from Figure 8 in Nature Communications (2019), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (changes made: figure cropped and incorporated into composite). Bottom panel: Pathogenic missense variants identified in UNC13A overlaid on a domain schematic, highlighting a recurrent “UNC13A hinge” hotspot, together with a gene-wide tolerance landscape derived from population variation (MetaDome/gnomAD-based tolerance scores; red = intolerant, blue = tolerant). Reproduced/adapted from Asadollahi et al. (2025) licensed under CC BY 4.0 (changes made: figure cropped and incorporated into composite; author is a coauthor).

Minimal machinery. If you peel the synapse down to its essentials, there is a hierarchy. At the core is the minimal fusion machinery: the SNARE proteins Syntaxin-1, SNAP-25, and Synaptobrevin/VAMP2. These proteins assemble into a tight complex and force the vesicle membrane and the presynaptic membrane to fuse, enabling vesicle release. The discovery of this fundamental mechanism was recognized by the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to James Rothman, Randy Schekman, and Thomas Südhof.

Minimal release machinery. But a synapse is more complicated. Neurons do not just fuse membranes; they need to control vesicle fusion. This is where the priming proteins MUNC13 and MUNC18 come in. These proteins decide whether SNARE assembly can even begin. UNC13A is the human gene that encodes neuronal MUNC13 (MUNC13-1 in most synapse schematics). And MUNC18 is encoded by STXBP1, a gene we know extremely well through our work in this space at our Center for Epilepsy and Neurodevelopmental Disorders (ENDD). In other words, UNC13A is not a newcomer; it sits directly next to STXBP1 in the same priming pathway, acting on the same Syntaxin-centered gate that determines whether a synapse can become competent for release.

Minimal synapse. The next level of complexity is the minimal synapse, which includes active zone scaffolding and Ca²⁺ channel coupling. The synapse needs a release site with geometry, it needs calcium entry that is physically close enough to trigger release, and it needs vesicle pools that can be mobilized and replenished. If the minimal fusion machinery explains how membranes can merge, and the minimal release machinery explains who grants permission, the minimal synapse explains where and when fusion becomes meaningful.

Active zone scaffold. The active zone includes proteins that were initially new to me. RIM (RIMS1/2), RIM-BP (RIMBP1/2), and ELKS/CAST (ERC1/2) are needed to position vesicles and channels into a functional unit. And then there are proteins that we know from neurogenetics, such as Bassoon and Piccolo (BSN and PCLO). We recently discussed Bassoon and its discovery as a neurodevelopmental gene with a wide phenotypic range.

Ca²⁺ entry. In addition to the active zone scaffold, the minimal synapse also needs its trigger. CACNA1A (CaV2.1) and CACNA1B (CaV2.2) channels are the critical synaptic calcium channels. CACNA1A is a common neurodevelopmental gene, associated with developmental differences and ataxia. In addition, as we have highlighted in previous blog posts, gain-of-function variants can result in epilepsy and hemiplegic migraine. We recently contributed to a study assessing the function of more than 40 variants in CACNA1A, and this study deserves its own future post.

Vesicle tethering, docking, and pool organization. Finally, our minimal synapses need logistics. Synapsins (SYN1/2) organize reserve vesicle pools and help mobilize them. Rab3 participates in tethering and presynaptic vesicle organization. Without this additional layer, the release machinery might work once, but it cannot work repeatedly. Taken together, we can think of the synapse as a functional hierarchy, starting with the minimal fusion machinery and then building up to the minimal release machinery and the minimal synapse.

UNC13A as a disease gene. The recent publication in Nature Genetics by Asadollahi and collaborators does something that is still surprisingly rare in synapse disorders. The authors define a clinical spectrum with enough detail to allow genotype–phenotype correlation. Rather than simply presenting UNC13A as a gene for developmental disorders and seizures, the study places individuals into distinct patient subgroups that differ in developmental trajectory, movement disorder burden, and epilepsy severity based on the functional consequences of the UNC13A variant. Across the cohort, shared features include global developmental delay and/or intellectual disability, with additional neurologic manifestations that cluster around two themes common in synapse disorders: epilepsy and movement disorders, including ataxia, tremor, and dyskinesia. A subset of individuals has a severe early-onset presentation with developmental stagnation, and some individuals passed away in early childhood. This emphasizes that UNC13A-related disorders occur on a spectrum from neurodevelopmental disorders to developmental and epileptic encephalopathies.

Patient subgroups. The most helpful element of the study by Asadollahi and collaborators is its subdivision of UNC13A-related neurodevelopmental differences into clinical categories that map onto functional classes of variants. The authors propose three major phenotypic groups. Group A is characterized by severe neurodevelopmental impairment and early-onset epilepsy due to biallelic loss-of-function variants. Group B includes individuals with less prominent developmental differences but with ataxia, tremor, and dyskinetic movements. These individuals carry recurrent variants that lead to gain-of-function. Finally, individuals in Group C have the least prominent developmental differences and variable types of epilepsy. In this group, missense variants lead to dysregulation of UNC13A function. However, putting my ClinGen hat on, it is not fully clear to me whether this dysregulation represents partial gain- or loss-of-function. In summary, UNC13A-related disorders involve different disease mechanisms, including both loss- and gain-of-function processes, resulting in distinct phenotypes.

What you need to know. This recent publication in Nature Genetics by Asadollahi and collaborators places UNC13A beside STXBP1 on the priming axis of synaptic release—the molecular gate that determines whether SNARE fusion can proceed. UNC13A-related neurodevelopmental disorders emerge when the set point of the priming gate is shifted, and the authors suggest that both loss- and gain-of-function variants in UNC13A can result in neurodevelopmental disorders, epilepsy, and movement disorders. The discovery of additional synapse disorders not only highlights the clinical overlap between these conditions but also paints a more comprehensive picture of how changes in key steps of vesicle fusion result in disease. This insight is critical, as it represents one of the first steps toward targeted treatment strategies for synaptic disorders.